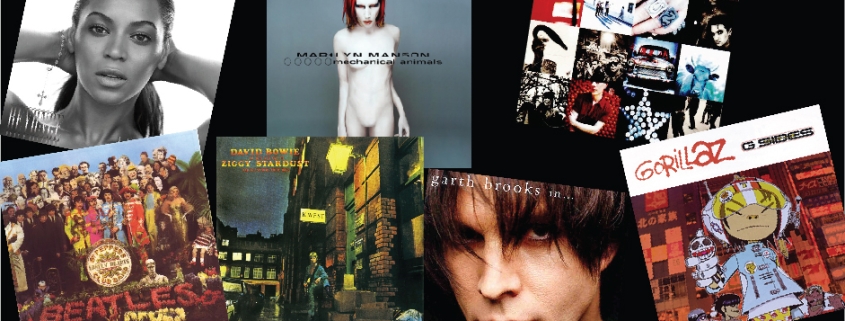

SCHIZOPHONIA! An Intro to Music’s Alter Egos

Countless musicians have created personas for themselves— that’s par for the course—but only an elite few have had the vision and testicular fortitude to assume an entirely new identity midstream. Robert Cherry unmasks the best—and the rest.

The biggest barrier to a creative breakthrough could be staring you right in the face. Robert Cherry explores a radical approach shared by a creative elite—a method, strangely enough, you yourself have already practiced.

“We really hated that four little mop-top boys approach. We were not boys, we were men. It was all gone, all that boy [expletive deleted], all that screaming, we didn’t want it anymore.” —Paul McCartney*

Want to take your creativity to new heights? Get rid of yourself. That might sound bonkers, but it’s actually one of the more common ways creative giants (J.K. Rowling being the latest) have worked themselves out of ruts and transcended personal limits. Ernest Hemingway… Marcel Duchamp… David Bowie… all have assumed entirely new identities at crucial points in their careers to create some of their most innovative and enduring work.\r\n\r\nTake, for prime example, the Beatles. By 1966, the world’s largest rock band had reached an impasse. Feeling imprisoned by fan expectations and frustrated by the screaming-ops their live performances had become (“We were turning into such bad musicians because the volume of the audience was always greater than the volume of the band,” Ringo Starr told The South Bank Show in 1992), the group famously retired from touring and exiled themselves to their run-down playground, Abbey Road Studios.

But escaping from the road wasn’t the key to their creative freedom. The barriers they were feeling weren’t physical barriers but mental barriers. As a cultural phenomenon, their image had become fixed in the public eye as “a mop-topped English pop quartet… who set the foot of the world a-tapping with their catchy melodies, their wacky Liverpool humor and their zany, off-the-wall antics,” to quote Beatles spoof The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash. Yet, paradoxically, they were also expected to wow with each new release, continually redrawing, as they had on previous releases like Revolver, what was possible for rock music.

To add to the pressure, the group’s leaders—Paul McCartney and John Lennon—were engaged in a friendly rivalry with the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, who had recently unveiled his own creative high watermark, Pet Sounds. To compete—as they were driven to do—the Beatles required a fresh approach to overcome burnout, rekindle their passion and remain relevant in an increasingly experimental field.\r\n\r\nFortunately, highly creative people can usually find highly creative ways to inspire themselves and focus their supporting cast. While John Lennon is often credited with the Beatles’ more out-there experiments (he once lobbied to sing the lead vocal for “Tomorrow Never Knows” while suspended upside-down from the studio ceiling—you know, to capture that holy-man-on-the-mountain vibe), it was Paul McCartney who arrived at a breakthrough this time (and many others).

“I thought, ‘Let’s not be ourselves,’” he told Barry Miles in Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now of the a-ha moment. “‘Let’s develop alter egos… it won’t be us making all that sound, it won’t be the Beatles, it’ll be this other band, so we’ll be able to lose our identities in this.’

The result of the experiment? Clinical insanity and commercial suicide. Kidding. No, actually it was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album that, almost 50 years later, still routinely tops popular and critical lists of the best/most important rock albums ever made.

While the alter-ego concept only extends to the album’s iconic cover and three of its tracks (the title song, its reprise and the “Billy Shears”-fronted “A Little Help From My Friends”), the exercise helped to simultaneously focus the band and free them to experiment with songs, sounds and approaches they might have otherwise dismissed as “not Beatles.”

The alter ego they selected was inspired by McCartney’s visit to San Francisco, where bands from the emerging psychedelic scene favored more esoteric names (like “Fred and His Incredible Shrinking Grateful Airplanes,” as Lennon once spoofed in a 1980 interview with David Sheff for Playboy), and happenings took on the flavor of ye olde timey carnivals—on electric sugar cubes and jazz cigarettes. Winging his way back to London, McCartney flashed on his band’s new identity—Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

“Everything about the album will be imagined from the perspective of these people,” he told The South Bank Show, recalling the conceptual approach. “So it doesn’t have to be us; it doesn’t have to be the kind of song you want to write, it could be the kind of song they might want to write.”

Always up for experimentation, his bandmates, producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick embraced the concept and “from that moment on it was as though Pepper had a life of its own,” as Martin recalled in his autobiography, All You Need Is Ears.

History credits the album with numerous breakthroughs in pop music, all of which are commonplace today, from the use of the studio as an instrument in and of itself (multitrack recording effects, sound collage) to genre mash-ups (their embrace of traditional Indian music and instrumentation and their ongoing incorporation of European classical elements) to the concept of the concept album itself.\r\n\r\nIn fact, the experiment even suggested a new business model for the road-weary band. In McCartney’s grand vision for the project, “the record could go on tour,” not the band, as he recalled on The South Bank Show, leaving the Beatles free to… well… take a Magical Mystery Tour and then reinvent themselves yet again on the back-to-basics White Album.

Of course, you and I are not Beatles. But we do share the same barrier the band faced every time we approach a new creative project. When we sit down to create, the first limit we encounter is self-perception and that creativity killer, the “not you.” In fact, some of us might not even sit down to create in the first place because “you” are not the sort of person who creates.

“Persona is a word that derives from the Latin for ‘mask,’ but often refers to the practical and successful personality we use most of the time in the workplace and social relationships,” writes art therapist Cathy Malchiodi, Ph.D., on the use of mask making for healing transformation, in Psychology Today. “It’s a bit like a facade we start to develop in childhood when we get approval for behaving in certain ways.” And if creativity isn’t one of those reinforced traits, it can be repressed and left to atrophy.

But even if you know you’re the sort of person who creates, you might sit down with limiting expectations about your role in the process, for instance, I’m the writer, I only write, or I only write in this style. Or, you might think there’s a “proper” way to approach the act, like sitting down to start in the first place or even having a clear starting point (in my experience, most creative breakthroughs happen off the clock and in a mental space that operates outside linear time; and no, I haven’t been puffing jazz cigarettes).

We’re also limited by the ego’s desire to protect our self-image so we don’t appear foolish and therefore vulnerable to others. Yet the thing people most react to in any creative work—be it music, comedy, art, writing, filmmaking or even marketing—is emotional honesty. You have to access and reveal a deeper part of yourself to connect with others in a deeper—and hopefully lasting—way.

Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, to take but one example, has charmed its way into 40 million households since its release in 1977, because it’s a highly tuneful, extremely well-crafted aural soap opera depicting the band members’ dissolving relationships (no alter egos were involved in its creation, but the approach might have come in handy for the famously fractious, unfocused and protracted sessions for its follow-up, Tusk). As singer-guitarist Lindsey Buckingham told Mojo’s Mark Blake in 2012, “what makes Rumours so attractive to people is the fact that we were making this music while all our hearts were breaking.”

And they didn’t hold back from expressing that heartbreak, even when—or maybe especially when—they knew it would sting the person with whom they were sharing a mic at the time. “There is so much truth going on in all those songs that there is no way you change them,” Buckingham told Blake, when asked about a line his ex Stevie Nicks found especially hurtful (“shacking up is all you want to do,” from “Go Your Own Way”).

So how do you go about silencing the “not you” and revealing a deeper side of yourself? First, by acknowledging the potential burden and limits of self-image, as McCartney did. Art therapist Malchiodi, for instance, recommends patients create a life-sized mask, with the outside symbolizing “how others see you” and the inside representing “how you really feel inside.” The creative exercise helps “bring to consciousness,” in her words, both one’s public persona and one’s unfulfilled potential.

For the purpose of stretching your creativity, the next step is something you practiced as a child. Remember playing make-believe, say, crafting a pirate hat and eye patch out of craft paper, borrowing a clip-on earring from your mother’s jewelry box and hitting the Seven Seas in a whiskey box? No? Really? Just me, then? Well, insert your own childhood role-playing games and you get the idea.

Creating an alter ego is essentially the same exercise—bringing to life an unexpressed side of yourself—only now you’re using this new identity to approach your work in a fresh context around which you base creative decisions as the creative process unfolds. In addition, you’re suddenly free, paradoxically, to reveal more of your true self and take greater risks, because, the logic goes, it’s not you taking the chance, it’s him or her or it—whatever you call your new identity.

After all, there’s no worry of saving face when you’re wearing a mask